MK3|Oct. 17, 2025

Source: https://www.midwesterndoctor.com/p/why-the-bioweapons-research-industry?utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web

and what the WHO is doing to protect this grift now that the public is wising up to it.

Story at a Glance:

•The upper class has gradually shifted to controlling the populace through economic enslavement, the fear of an ecological disaster, and the fear of a disastrous pandemic which must be stopped at any costs.

•An immensely profitable industry has been built around these fears. Many notorious career scientists (e.g., Fauci and Hotez) depend upon this grift. Worse still, those fears have been used to create the justification we need to perform an endless amount of bioweapons research to “prevent” the next pandemic.

•That research is extremely dangerous and regularly leads to disastrous lab leaks which sicken and sometimes kill those exposed to the pathogens. While COVID-19 was the most consequential lab leak, many more preceded it, and prior to the pandemic (where everything got censored), the lab leak issue was widely discussed within the scientific community.

•Rather than acknowledge the problem (and stop the lucrative bioweapons research), the industry has doubled down on the importance of their research. This is analogous to how they actually discovered ways to treat these diseases with existing technologies (e.g., hydroxycholoroquine for SARS), but threw all of that to the wayside so more lucrative therapies could be sold to the public once an actual pandemic (COVID-19) started.

•Since the public is gradually becoming aware of what COVID cartel has done to us, they are switching to far more totalitarian methods to ensure they can continue their grift. We are at a pivotal moment to stop that, and that is why this series was written.

Recently, I completed a series about the deranged ravings and totalitarian aspirations of Peter Hotez. As I was finishing it, I came across an interview Brett Weinstein did with Tucker Carlson and immediately realized that the purpose of Hotez’s campaign was to pave the way for the WHO’s abhorrent plan for the world.

After seeing it, I discussed this with a colleague who remarked “did you know Meryl Nass has been funding a non-profit to stop the WHO’s pandemic treaty, has been going around the non-stop speaking to parliaments andi is successfully convincing government after government to back out of it?”

I thought this was remarkable and decided I needed to put together a series about it. Now that I’ve gone through everything, I have reached three key conclusions about all of it.

•What the WHO is planning for us is truly horrifying (and simultaneously from a sociological point quite fascinating).

•Because so many vested interests are tied into the WHO’s pandemic treaty, that ship has a lot of wind behind its sails.

•The pandemic cartel is in a rather precarious position. Because of this, we have a unique opportunity to derail their plans, which Nass and others have thusfar done an absolutely brilliant job of pulling off.

Note: much of this article is sourced from Meryl Nass’s substack. Please consider subscribing and supporting her critical work.

The Billionaire’s Conquest

One of the lens I see the world through is “economic feudalism” which posits that the ruling class are trying to enslave the rest of the world by making them so impoverished they have no choice except to comply with whatever instructions their corporate overlords give them (e.g., vaccinate or lose your job and the ability to feed your family).

When you see the world through this lens, it is truly remarkable how methodical the billionaire class has been over the decades in monopolizing the world’s wealth and how many different institutions they’ve propped up who all support their agenda (e.g., consider how much unchecked power their transnational corporations have).

Because of this, there has been a general corrosion of many of the rights and freedoms and functionality we expect from democracies (or democratic republics) in parallel to a tidal wave of destructive corruption which has infested almost every institution. For example, in previous eras, even with sociopathic governments that viewed their citizens as entirely expendable, if corruption ran unchecked to the point it threatened the stability of the country, it would be rooted out. Yet, in the last few years, we’ve seen policy after policy be passed which benefit the billionaire class at the expense of everything else (e.g., our national economy has become much weaker since COVID-19).

As a result, a variety of institutions (e.g., the World Economic Forum) have been established which are controlled by the billionaire class and simultaneously wield a great deal of power throughout the “democracies” of the world but are simultaneously accountable to no one besides the wealthiest members of society. In turn, as you might expect, more and more of the world’s wealth is being hoarded by these oligarchs while everyone descends further into poverty.

For example, as a result of the COVID response the billionaires championed:

•We witnessed the largest transfer of wealth in history. From 2020 to 2021, billionaires went from owning slightly over 2% of the global household wealth to 3.5% of it.

•One third of American’s small businesses closed. These were often sources of generational wealth and more importantly, an alternative to corporate serfdom (enslavement).

•There was a “historically unprecedented increase in global poverty” of close to 100 million people, and a 11.6% global increase of extreme poverty. The impact of this is hard to even begin to put into words.

•150 million people no longer had the food they needed. The magnitude of this wave of global starvation in another thing that is almost impossible to put into words.

Note: these individuals are commonly referred to as “globalists” because they favor global institutions (which they control and thereby bypass the democratic process) having as much power as possible. I also believe the globalists have no loyalty to a specific nation, which helps to explain why they will prioritize their own interests over the national interests.

Peter Hotez

Peter Hotez frequently earned the ire of the vaccine safety movement because he would publicly insist there was no link between vaccines and brain damage (e.g., autism) and would be constantly be given an unchecked platform to air his beliefs. Much of this was based on his claims that his autistic daughter did not develop autism from a vaccine (even though his book demonstrates he missed the classical clinical signs of a vaccine brain injury which coincidentally preceded her developing autism).

Note: the evidence vaccines cause autism, and the mechanisms through which they do (which have been used to successfully treat autism) are discussed in further here.

After he understandably upset a lot of people with vaccine injured children by doing this, Hotez used the animosity he received to justify branding himself as an expert on the antivaccine movement. Before long he embarked on a speaking tour (e.g., that is where his infamous Joe Rogan clip comes from) to argue that anyone espousing antivaccine views needed to be censored from Amazon’s book store and the internet.

At the time, I thought he was a clown (e.g., consider the above video) and didn’t put much thought into him. However, not long after his tour, COVID happened and the unprecedented censorship Hotez had called for was enacted across the internet, which in turn lead to the government’s narrative (which was completely at odds with reality) becoming the accepted gospel, while critically important information (e.g., safe and effective treatments for COVID or the innumerable dangers of the vaccines) was kept away from the public.

During Trump’s presidency, Hotez was relatively quiet and most of what he said was critical of the administration’s COVID response (e.g., he testified in front of congress and gave media interviewsstating why it was a bad idea to make a rushed coronavirus vaccine). However, near the end of Trump’s presidency, he penned a piece arguing that to convince the public to take the vaccines, the presidential administration would need to appoint a national spokesperson who promoted the national vaccine policy.

Once Biden became president, Hotez became a constant fixture on national television who echoed whatever the current vaccine talking points were (e.g., everyone has to get vaccinated or boosted no matter what) and as many have observed repeatedly contradicted himself (which was somewhat necessary as he was pitching a fraudulent product to the public). In turn, Hotez (who was not at all photogenic) became an object of ridicule by the political right.

Unfortunately, Hotez then moved beyond simply pitching products to directly attacking anyone who didn’t want to buy them and began proclaiming the “anti-vaxxers” were mass murders (as they were preventing people from getting the “life-saving vaccines”).

Note: most of the evidence for this claim came from the CDC’s decision to classify many vaccinated individuals who were hospitalized as “unvaccinated,” which not surprisingly, led to far more of the deaths occurring in the “unvaccinated” as hospitals were the most common site of death from COVID-19.

Before long, he moved to claiming criticizing prominent scientists (e.g., Fauci who lied at a similar to Hotez) should become a federal hate crime. Finally, over Christmas 2022, we decided we needed to do something after the W.H.O. put out a professionally produced tweet of Hotez calling for governments of the world to mobilize against the “anti-vaxxers” and neutralize the dire threat we posed. This prompted me to do some digging into Hotez’s background (e.g., we sent out the infamous clip of him Joe Rogan at the time).

In doing so I found:

•Hotez’s entire career was financed by the pharmaceutical industry and the most notorious globalists (e.g., The Gates Foundation).

•He had received over 100 million dollars in grantsto develop “vaccines for poverty” even though after decades that research hadn’t gone anywhere.

•Hotez constantly used all the classic meaningless buzzwords seen throughout left-wing academia and frequently espoused their utopian (but delusional) ideologies.

•While Hotez vociferously attacked anyone who proposed that COVID-19 was leaked from a lab, prior to COVID-19, Hotez had been the recipient of a 6.1 million NIH grant to develop a SARS vaccine for the possibility a weaponized SARS virus was accidentally leaked from a lab. As it just so happened, as part of that “research” he funded gain of function (bioweapons) research at the Wuhan lab.

From all of this, I concluded that Hotez’s primary motivation for everything was similar to what is seen throughout academia (where one’s lifeblood is the grants they receive)—he just wanted to attract as much funding as possible for his projects. In turn, by constantly being given the opportunity to plaster himself on the left-wing networks and brand himself as both the poor scientist being harassed by the “anti-vaxxers” and a humanitarian struggling against all odds to produce lifesaving vaccines for the third world, he was sure to attract rich liberal donors who had no actual understanding of the money pit his research was.

Note: this is why I believe Hotez rejected Joe Rogan’s offer for Hotez to publicly debate RFK Jr. in return for 2.62 million dollars being given to a charity of Hotez’s choice, as doing so would have required Hotez (who never takes questions from a critical audience) to have exposed himself and jeopardized his far more lucrative grift.

Hotez et. al

When I looked into Hotez, one thing kept on bugging me. Because he is disheveled, clearly unhealthy and socially awkward, each time he speaks publicly, he doesn’t look good—to the point he appears so uncredible he often succeeds in convincing in people to do the opposite of what he’s proposing (e.g., the previously shown Rogan clip was seen by over ten million people and inadvertently ended up being one of the most persuasive arguments against vaccination in modern history).

This in turn raises a simple question. Why does everyone keep supporting him (to the degree to which the media and scientific profession circles wagons around Hotez is astounding) rather than just finding a better national vaccine spokesman who actually gets people to vaccinate?

As I dug through Meryl’s research, I at last found the answer—there are a lot of other (much less visible) people in prominent positions throughout the medical industrial complex who are just like Hotez. Since these individuals have a massive sway over both academia and the media (including Big Tech), they hold a tribal loyalty to protecting Hotez.

Amongst other things, these individuals tend to:

•Be neck deep in disastrous gain of function (GoF) research.

•Use meaningless progressive buzzwords to promote their agenda.

•Be repeatedly reward and promoted by our institutions despite their poor (and often disastrous) performance. The last point is important, because we assume our experts are selected on the basis of their competency, but in reality, much of their selection is a result of their loyalty to business interests.

For example, the disastrous lockdowns which swept the world were based upon the dire models a prestigious epidemiologist (Neil Ferguson) from a prestigious (Gates funded) institution put forward, which argued that millions would die were harsh lockdowns not implemented. In reality, Ferguson’ projections were wildly inaccurate (as it was later shown they overestimated the risk of death by between 298% to 1798180%), Ferguson had a long history of making wildly over the top projections about upcoming infectious diseases, and when exposed a basic degree of scrutiny, it was clear his COVID lockdown model was nonsensical.

Nonetheless, no one who raised clearly valid objections against his model’s shortcomings was listened to, and in many cases people who proposed alternative (and much more sane options) were instead relentlessly attacked by both the governmentand the press. However, unlike Hotez, since Ferguson didn’t plaster himself in front of the media, most people aren’t aware of him or the fact he’s done far more damage to the world than Hotez ever did.

Since no clear term exists for these “progressive” grifters who will happily sell out their country to the medical industrial complex, I’ve decided to refer to them as Hotez et. al (especially since many of them are friends and they frequently co-author paper together).

Perpetual Wars

Over the decades, I’ve read document after document allegedly written by an elite think tank (policy planning group) which argued that the most effective way to control a population is with a war. This is because war causes the economy to be shifted to wartime production (which is very profitable for those positioned to take advantage of it) and the population can be easily led to unify behind fighting the own war rather than focusing upon their own interests (e.g., saying no to the government exploiting them).

The issue with this approach was that because war technology has become so much more powerful (e.g., nuclear weapons) it’s simply not possible to wage large scale wars anymore without them being catastrophic for both sides. As a result, the general approach taken was to switch from real wars to abstract wars, as these could get all the benefits of a sustained war without jeopardizing the ruling class’s interests.

Over and over, the three candidates I saw proposed for this war were:

•An illness or disease (typically one which was infectious).

•Terrorism.

•An environmental disaster.

Note: while I never saw “racism” or “bigotry” proposed in those documents, given the cultural push for DEI, I suspect it may have since become a serious consideration. Conversely while drug prohibition and preventing illegal immigration meet the necessary criteria to become a pseudo-war, I don’t believe they have been because the billionaires profit too much from them continuing.

Throughout my entire lifetime, the media has worked day in day out to stoke the fears of an environmental cataclysm or a deadly plague sweeping the world, while more recently (after 9/11) it worked to do the same thing with terrorism.

From watching each of these, it became very clear to me the goal was never to solve the problem, but rather the define it as vaguely as possible so that it could morph into whatever the ruling class needed to fulfill their agenda. For example, as discussed previously, legitimately environmentally friendly energy technologies have existed for decades which could easily give the world access to clean and affordable energy. However, each of those technologies has been stonewalled, and instead a variety of expensive (and environmentally damaging) technologies have instead been relentlessly promoted by our institutions.

Note: this is analogous to how countless effective (and proven) treatments for still “unsolved” diseases have been ruthlessly suppressed by the medical established, while innumerable lucrative (but unsafe and ineffective) therapies are expedited through the approval process. While I’ve called out “Hotez” (and his compatriots) for grifting, the reality is that there are far larger grifters within our current economic system.

Doublespeak

George Orwell’s classic 1984 describes the totalitarian nightmare he foresaw from communism merging with modern technology that made unparalleled mass surveillance possible. Within that society, the citizenry were constantly required to believe with absolute conviction things they had to know were false.

For example, their country’s government controlled the population by constantly being at war with one of the two neighboring superpowers (which in turn necessitated them having a seething hatred towards their enemy), but frequently, their nation would switch to being at war with the other country (while their previous enemy became their ally). In turn, the citizenry had to legitimately believe “we have always been at war with Eastasia” once they were told to.

Note: this is similar to how so many people still trust Hotez or Fauci despite the fact both individuals have clearly lied to them throughout the pandemic, or why some are still vaccinating despite the vaccines having failed to do everything they were promised to (which remarkably, many now deny was never promised despite the fact they had previously pushed the exact same lies on their peers).

A key aspect of doublespeak was for phrases to mean the opposite of what they said, and for the subconsciousness of each speaker (or listener) to grasp the actual meaning (so they could do what the government needed) without them consciously realizing what they were doing.

Over the last few decades, we’ve seen progressively evolving discourse (which was originally known as “postmodernism”) infect academia and gradually diffuse into the broader culture. Like doublespeak, this dialectical style uses a variety of nice sounding (and hard to understand) buzzwords to conceal a variety of depraved ideas (e.g., the traditional social structures which have long protected us must be abolished, traditional Europeans and Americans are a scourge upon the world, and that much of the human population must be culled for the greater good).

Note: one of the many harmful “doublespeaks” we are now stuck with is bioweapons research being euphemistically referred to as gain of function research.

To enshrine this modern form of double speak, the billionaire class has put a lot of working into buying out academia and the media. For example, most of the world’s media is owned by six corporations(whose CEOs belong to the billionaire’s globalist organizations) and likewise, as researchers recently discovered, all the major medical information resources (like the journals who continually refused to published lifesaving information throughout the pandemic) are under the influence of the WEF.

These assets in turn have been leveraged to create construct after construct that firmly established their utopian form of double speak upon the world. For instance, when I began reviewing the work of Hotez et. al, I kept on noticing they used similar terminologies and often referenced each other to establish the validity of these terms.

Note: until recently, those assets likewise made it possible to ensure no dissenting narrative which threatens the legitimacy of this new doublespeak could ever be presented to the public.

In short, “Public Health” has transformed into a global racketeering operation where it is very difficult for legitimate science which advances humanity to see the light of day (hence why groundbreaking innovations in science have largely disappeared despite us now spending far more on our scientific apparatus). The public face of this operation are Hotez and his compatriots, while the private (and actual) face of this operation are the oligarchs that fund it. Beyond being the largest of its kind in history, what makes it so unique is the fact that it’s very hard to see because it’s been meticulously cloaked behind a lot of doublespeak that seems like something only a good person would support (e.g., who doesn’t want poor people to healthy?).

One Health

In 2004, an international (globalist) conference was held which stated public health needed to be integrated with environmental management (termed “One Health). The key theme of this conference was that given the dire urgency of the environmental and biological threats we faced, all major “One Health” decisions would need to be made by a panel of multidisciplinary experts.

On the surface (especially given the utopian language they used) this sounds like a great idea. However, given how easy experts are to buy off (as we all saw throughout the pandemic), it was clear to any seasoned observer that One Health was simply an attempt to merge the war on infectious diseases with the war on future environmental catastrophe and have “One Health” usurp the ability of the common people to speak out against it—as under the incredibly broad definition of “One Health,” almost every aspect of our lives was something which could be regulated under it (e.g., you can’t live here because it might increase the chance of you coming in contact with a wild animal that could spark a pandemic).

Since that time, more and more efforts have gone into propping up the W.H.O’s One Health brand and the term has gradually infested all the “elite” publications. One of the saddest things about this is that this corruption has made a lot of the “charitable” non-governmental the world relied transform into ones that harm the people they serve.

For example:

•The Gates Foundation (and many other similar organizations) have attempted to “fix” global hunger by replacing their traditional (and sustainable) forms of agriculture with chemical heavy GMO based farming. This frequently leads to food shortages (as those products are far more expensive) but makes a lot of money for the American corporations pushing these products by transferring the wealth to them that previously would have gone to local community farmers.

Note: this is similar to how traditional (and environmentally sustainable forms) of food production such as grass fed beef and even home gardening have been relentlessly demonized by the globalist publications while far less healthy (and simultaneously more environmentally costly) approaches like bugs and or soy are continually promoted.

•As friends working at the WHO shared, the WHO used to provide a variety of important public health measures to the third world (e.g., mosquito nets or clean water). However, after globalist money entered the organization (e.g., Bill Gates is now their largest sponsor) that focus has been transformed into providing as many vaccines as possible to the third world while simultaneously neglecting numerous other critical public health strategies.

•The UN was originally created for the purpose of providing an international body which could facilitate dialog (and policies) that would prevent future wars. However, rather than fulfill its actual role (e.g., the UN green-lighted the fraudulent invasion of Iraq, while more recently the UN repeatedly ignored Russia’s pleas for Ukraine to stop conducting actions which directly threatened Russia’s national security—which eventually led to Russia starting a war to stop those actions), the UN has instead focused on advancing a variety of “progressive” ideals (e.g., forcing One Health upon the world) which have nothing to do with why it was originally created.

In short, there is a lot of money and power behind the One Health Agenda. For example, American’s 2023 National Defensive Authorization Actcontained a provision to advance the “One Health Approach” and provided at least one billion a year to support in alongside a few related globalist organizations.

Sadly, as we will discuss in the second half of this series, most of “One Health” is a series of deceptive promises wrapped in doublespeak which simply serve the billionaire class and do anything but promote health.

Bioweapons Research

When World War 2 ended, the US chose to “pardon” many Nazi and Japanese scientists in return for them working for us. In this process, we brought over many notorious bioweapons specialists (e.g., there was a Japanese unit that regularly experimented upon Chinese prisoners) that gave birth to an American bioweapons program.

Eventually Nixon decided an international treaty needed to be created to outlaw the use of bioweapons (which may have been a product of wisdom on his part, or as others argue because biological weaponry was the one area where the USA did not have an edge on the rest of the world so it was to our detriment if the technology became widely used). Unfortunately, The Biological Weapon’s Convention had a major loophole—it permitted the bioweapons work to continue if it was for “prophylactic, protective or other peaceful purposes.”

As a result, the US never stopped researching bioweapons (e.g., we have a military facility dedicated to it). Eventually, modern genetic engineering made it possible to create much more advanced bioweapons (e.g., genetically targeted ones) and the process become complex enough for us to regain technological superiority in the area which led many (e.g., Hotez et. al) to receive the funding to begin explore every possible way a pathogen could harm others and how they could be genetically modified to become even more dangerous.

A major problem with this approach was that since the bioweapons research community often conducted their experiments in a fairly reckless fashion, again and again, what they made would either reach the general population or a major catastrophe would be only narrowly averted. For example:

•In 1950, the US Navy covertly sprayed what they considered to be a harmless bacteria at test sites through the San Francisco Bay Area to see how easy a bioweapons agent was to deploy against a population center. It was then discovered that the bacteria was not harmless, and caused a variety of fatal infections. It has since become endemic to the area (e.g., it thrives in warm and moist environments like hot tubs). In 1977 (since infections from it were still occurring) a Senate hearing was conducted where it was discovered that between 1949 and 1969 the US military had conducted 80 open air tests of bacteria that at the time were believed to be harmless.

•In 1966, a leak of a less dangerous smallpox strain from an English biolab infected one person who went on to infect 65 more. Twelve years later, another leak occurred from that same lab and killed someone working above the lab. Similarly, in 1971, weaponized smallpox escaped a Soviet lab killing three.

•In 1975, Lyme disease emerged in the immediate vicinity of a US government facility which was working on weaponizing the same bacteria which caused the disease.

Note: the case Lyme disease was a lab leak is quite strong.

•In 1977, the H1N1 flu virus that was blamed for the devastating 1918 Spanish flu pandemic reappeared in China and swept across the globe. Scientists sourced this outbreak to an escape of a reconstituted Spanish Flu from a laboratory freezer in the southern USSR or northern China.

•In 1979, weaponized anthrax spores were accidentally released from a Soviet military research facility. At least 68 civillians died, although the total number of deaths will never be known since the government covered it up.

•In 2001, letters laced with Anthrax circulated the US, killing 5 and sickening 17. When the pathogen in those letters was examined, it was discovered to be a weaponized strain which only existed in a few US bioweapons labs.

•Numerous SARS lab leaks have happened since it first emerged in 2002 (e.g., 1, 2, 3, 4, 5 6), some of which turned into broader outbreaks.

Note: coronaviruses (like SARS) are one of the easiest viruses to perform GoF research on, and hence one of the most commonly modified pathogens.

•A case can be made that the devastating 2014 and 2016 Ebola outbreaks leaked from a CDC lab in Africa which studied these pathogens.

•A case can also be made monkeypox originated from a lab as it was found to be 99.9% identical from Israel’s 2018 lab strain.

Furthermore, devastating leaks we are still affected with to this day also occur outside of bioweapons research. For example:

•Between 1955-1961, the cancer causing SV-40 virus spread throughout the population from contaminated polio vaccines. However despite the government receiving warnings about this, it still chose to release the vaccine (as they were fully committed to the vaccine program). Once SV-40 entered the population, many physicians observed a significant increase in solid tumors (e.g., sarcomas) and renal diseases.

•In 1956, RSV (the virus we are now seeing the vaccine industry move to monetize) emerged. The previous year, a respiratory virus outbreak occurred in a chimpanzee colony at a military research facility that infected a labworker with a new respiratory virus he transmitted to other personel there. Shortly after, the human disease RSV emerged, and was largely indistinguishable from the initial infection a year before.

•In 1967, simultaneous lab leaks from African green monkey colonies in Germany and Serbia caused local outbreaks of the highly lethal Marburg Virus (which is very similar to Ebola).

•A strong case can also be made that HIV emerged through contaminated vaccines given in Africa, Haiti, and New York (the London Times even wrote an article about it).

Note: To provide further context to the above video, I had a colleague who knew a few of the participants in the original hepatitis B vaccine trials. He shared that the trial was done in a very hush-hush manner which made his friends suspicious they were being monitored for an undisclosed side effect and that the gay community was chosen for the initial test of the vaccine since they were less likely to have family members who would complain about any adverse effects. One of the most interesting discoveries they made was that HIV emerged shortly after the hepatitis B trials in the same cities where the Hepatitis B trials were conducted.

As each of the above cases indicate, lab leaks aren’t isolated events. Sadly, as many official sources show, lab leaks are quite common, but rarely reported (e.g., a recent Lancet paper looked at papers in a few languages published between 2000-2021 and was able identify reported 309 documented lab infections, 16 lab escapes and several deaths).

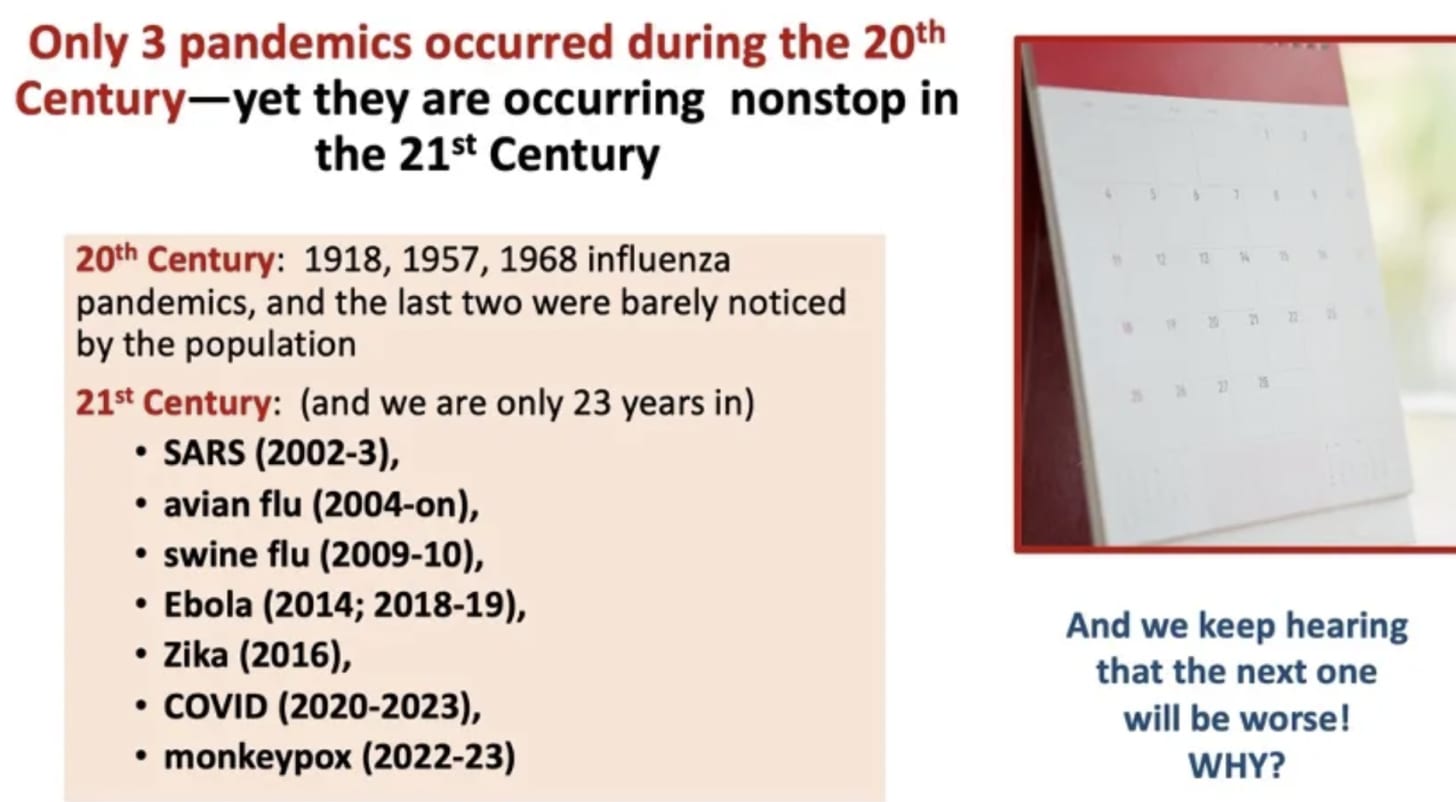

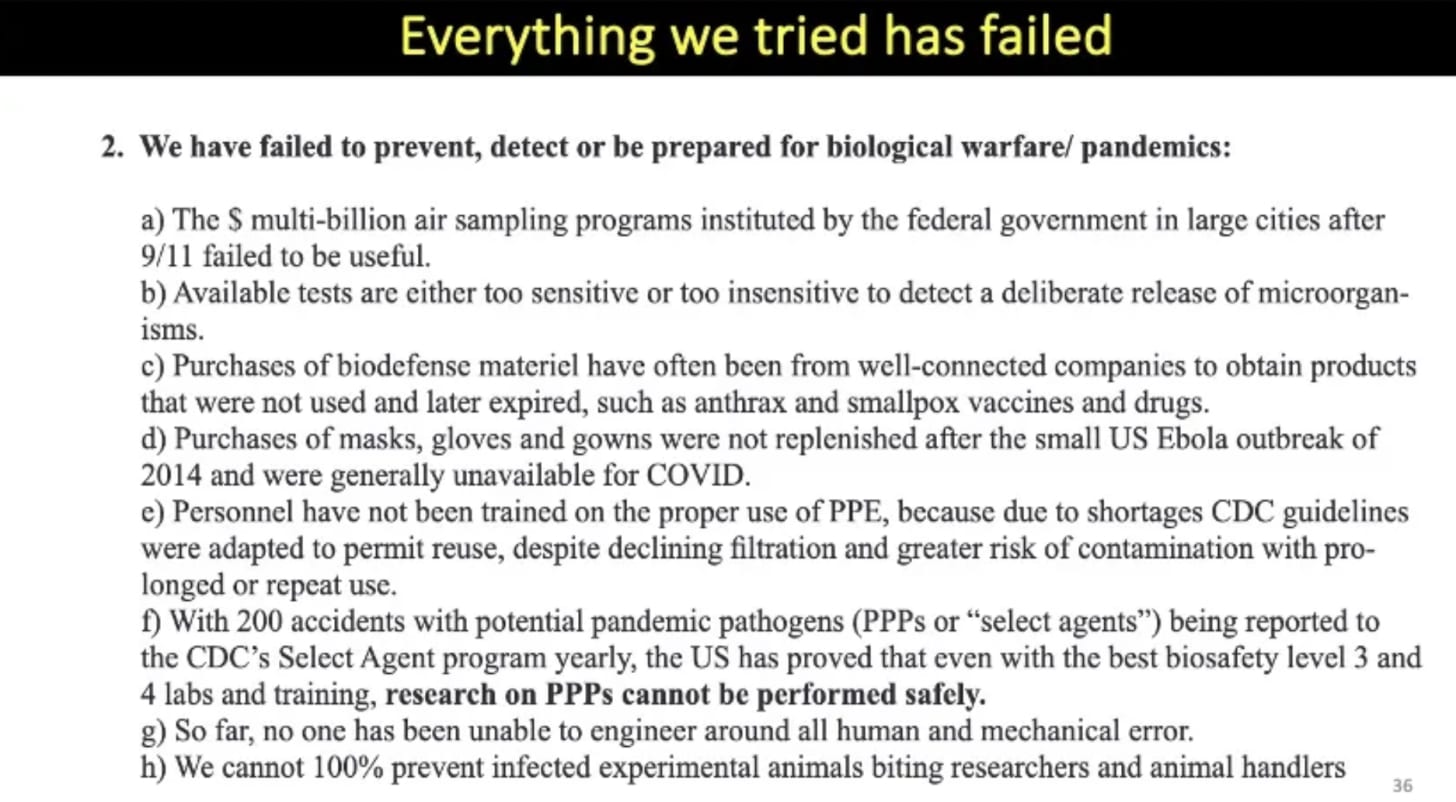

To quantify the magnitude of this problem, the Cambridge Working Group estimated in 2014 that potentially dangerous lab leaks occur, on average, two times each week in the US alone and by 2018 this number had risen to an average of four times per week. Meryl Nass concisely communicates the point with this slide:

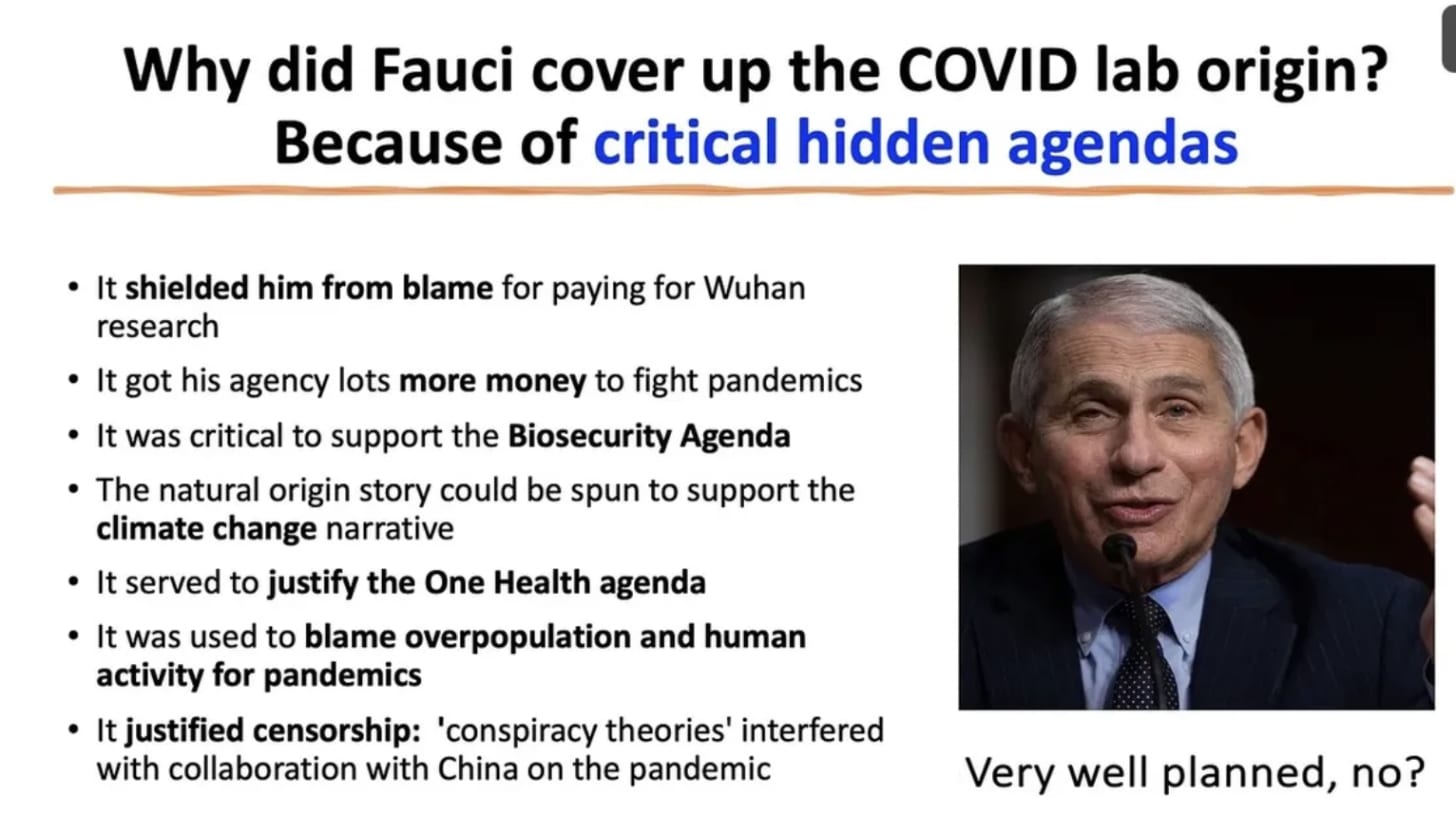

Note: prior to COVID-19, the scientific community was well aware of how dangerous GoF research was, and after a few prominent (and admitted) lab leaks happened over a short period of time, the scientific community petitioned President Obama imploring him to stop this research. Obama listened and in 2014 paused all federal funding on GoF research (and further highlighted the danger of GoF on the SARS virus). Fauci (who was likely profiting from performing the research for the DoD) got around this issue by outsourcing the research to Wuhan. Remarkably, the media has now made most of the world forget that prior to COVID-19, lab leaks were viewed as a frequent and legitimate problem.

Finally, it should be noted that (as we saw with COVID-19) this disastrous research often has widespread geopolitical consequences. For example, prior to beginning the most consequential war in the last 50 years, Russia repeatedly raised three major concerns to the United Nations. I hold the belief Russia was fully aware of how costly it would be to invade Ukraine, but ultimately did so because the Russians felt there was no other option to protect the national security of the country.

One of Russia’s concerns was the presence of US bio labs in Ukraine which Russia asserted were exposing Ukraine and Russia to harmful infectious diseases. While this was initially vehemently denied, the State Department later inadvertently admitted there were biolabs in Ukraine, and later, still confirmed the presence of these “peaceful” facilities (that it admitted were handling dangerous microbes) in a formal response to the accusation we were violating the bioweapon’s treaty.

While most of the debate on this subject focused around the idea this was all either Russian war propaganda to justify their invasion, or the even more speculative claim that the US was deliberately making bioweapons on Russia’s doorstep to covertly attack them, a third rarely considered (and more plausible) possibility also exists. The same disastrous “peaceful” research we’ve seen conducted throughout the world was also being conducted in Ukraine, and since the regulation was more lax there (as it was an out of sight out of mind location) accidental leaks were also happening.

Note: the most detailed summary I have found of the links between the US government and Ukraine’s biolabs can be found here (e.g., many members of the executive branch and US military were invested in those facilities). One thing that is important to note is that while “dangerous pathogens” were being stored at those labs, there was a “peaceful” justification for most of them being there. However, that is superseded by the fact lab leaks are a common occurrence even when facilities are not intending to do so.

The Bioweapons Indutry

All of this in turn begs a fairly straightforward question. If this research is so dangerous, why do people keep on doing it?

Presently, I believe it comes down to money. Since the scientific establishment (in lockstep with the media) has created a great deal of fear around these diseases, there is always a lot of funding for research to “protect” us from them.

Note: This is akin to how the CDC (with the help of the media) scares Congress each year about the next flu season to justify again receiving its bloated budget—even though, year after year, the CDC consistently fails to do anything which reduces the impact of the flu season.

In turn, since so much money has been invested into creating the facilities (and training a generation of scientists to perform the research there) there is a large community with an intrinsic self-interest in continuing this research as long as possible (and coming up with the justifications for why their employment is still necessary). Furthermore, a much broader industry has also been created to create countermeasures to those biological agents (e.g., there is a large contingent of people whose careers revolve around this in the Department of Defense—who amongst other things, prior to COVID-19, were responsible for the disastrous and completely unnecessary anthrax vaccines which permanently disabled around 250,000 servicemen).

In a previous article, I tried to expose the dangers of the statin drugs. To summarize it:

•There is actually very little evidence cholesterol causes heart disease.

•There is very little evidence statin drugs prevent heart disease or extend your life (e.g., assuming you “trust” the heavily biased industry trials, at best, lifelong statin use extends your life span by a few days).

•Since cholesterol is an essential nutrient, statin drugs frequently create significant side effects such as heart damage, muscle pain, weakness, loss of sensation in the body, and most importantly, cognitive impairment which can be a prelude to dementia.

Given all of that, it is quite remarkable that regardless of the criticisms raised, statins have remained as one of the most profitable drug franchises (as they are one of the most frequently prescribed drugs). One of the best explanations I’ve seen to explain this state of affairs is that because so much money (and time) was spent to create the mythology cholesterol causes heart disease, the medical industry will never let that investment go. I believe this is identical to the situation we now have within the pandemic industrial complex as so much money has been invested into its mythology over the decades. Consider that at this point how many people subconsciously believe a deadly plague may soon emerge from nature which will wipe humanity out, a belief which is what I believe ultimately persuaded many uninformed world leaders to comply with locking down their country to prevent the disastrous predictions of Ferguson’s nonsensicalCOVID-19 models.

Note: This situation is also encapsulated by the phrase no industry (or cause) can be depended upon to actually produce a solution for a problem it is tasked with solving. Instead, they simply come up with reason after reason to justify being given lots of resources to enact a piecemeal approach to “improving” (but never solving) the problem (and often instead make it become a bigger problem).

Of the lab leaks which have occurred, there was probably the strongest evidence tying COVID-19 to the Wuhan lab in China. For example, there had been many warnings (such as 2018 US State Department diplomatic cables) that a leak was likely to happen there, the outbreak emerged next to the Wuhan lab (which had a series of suspicious accidents prior to the outbreak), the virus had numerous characteristics that were not natural, a 2018 proposal was sent to the DoD to do coronavirus GoF research in Wuhan, numerous papers had been published by the lab [and US researchers tied to the lab] describing the creation of the exact same unnatural mutations which were later found in the virus (e.g., see here and here).

Note: much of this was well-known and was then compiled by independent researchers just a few months after COVID-19 began. One of the most recent (and detailed summaries) I have found of this can be found here (but it likewise doesn’t include everything as there is so much data tying COVID-19 to the Wuhan lab).

Unfortunately, due to the political implications of acknowledging US funding had created the most devastating pandemic in history, unlike the previously admitted SARS leaks, there was every incentive to deny this one originated from a lab.

One of the critical narratives the biosecurity agenda depends upon is the existential threat we face from animal diseases jumping to humans as this threat justifies paying them a lot of money to capture (and then experiment upon) animals from the most isolated places on earth (e.g., the leader of Wuhan’s lab would often travel to almost inaccessible caves in the middle of nowhere to collective coronaviruses from bats) and most importantly to perform endless GoF research.

This for example is why we have seen all the globalist institutions and the mainstream media continually warn us about the dire threat we face from “Disease X,” and the extraordinary lengths “brave” researchers are going to in order to scour the Earth for where that virus might be living.

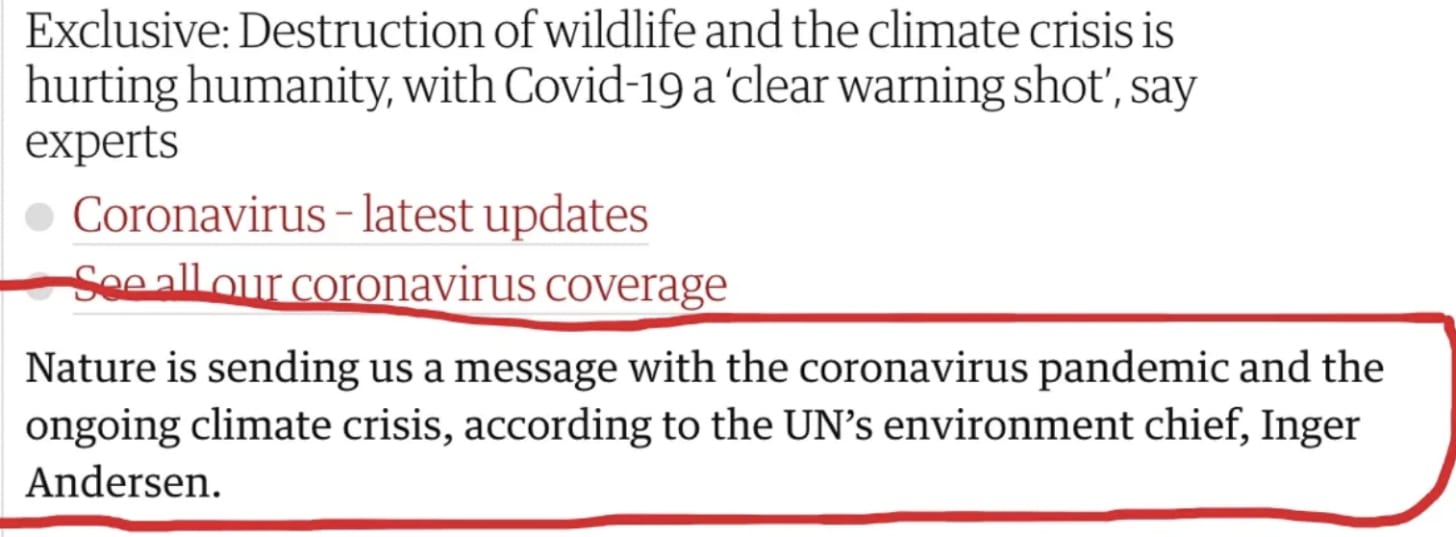

All of this in turn is predicated on the idea that we are at high risk of animals humans encounter transferring a deadly pandemic to them. However in reality, there is very little evidence natural zoonotic transmissions happens, rather as shown above, that transmissions typically is the result of (inevitable) lab accidents. However instead of coming clean about this problem, we are constantly bombarded with messages like this:

Note: I fully agree environmental destruction and habitat loss is a huge issue. However once people start to lie by claiming it will lead to a plague, it’s inevitable that they will also use their lie to violate basic human rights (e.g. arbitrarily deciding what food you are allowed to eat in the name of “One Health” or deciding where you can live).

Decades of Failures

As mentioned before, since the billionaires gained control of our medical apparatus, there has been a gradual trend towards individuals being selected for their position on the basis of their loyalty to business interests rather than competency to do the job well. So as you might expect, despite all the money they’ve received, they haven’t done their jobs very well:

However during COVID, we saw something remarkable. No only did the pandemic prevention perform poorly (e.g., they receive tons of money to survey potential pandemics, but still were telling America in February [as COVID was tearing through Europe] that COVID was not something for us to be concerned about), worse still, they actively sabotaged attempts to appropriately address it.

For example, it is well known that the best way to handle a pandemic is to repurpose an existing (FDA approved) drug, as unlike a new drug or vaccine, the repurposed drug:

•Doesn’t require a lengthy approval process.

•Doesn’t require a large investment from the manufacturer before it can enter the market.

•Is already known to be safe so testing can focus on efficacy.

•Its critical drug interactions are already known.

•An available supply of it already exists

•Is easy to mass produce since the production capacity already exists.

•Its affordable.

Note: prior to going public about the dangers of the vaccines, Robert Malone was heavily involved in working with the existing pandemic preparedness infrastructure to have a repurposed drug become the standard of care for COVID-19.

Fauci’s agency (NIAID), for example, was well aware of the value of repurposed drugs. Likewise, this is what Fauci shared in a December 2011 Washington Post article that was written to justify GoF research:

In addition, determining the molecular Achilles’ heel of these [GoF] viruses can allow scientists to identify novel antiviral drug targets that could be used to prevent infection in those at risk or to better treat those who become infected. Decades of experience tells us that disseminating information gained through biomedical research to legitimate scientists and health officials provides a critical foundation for generating appropriate countermeasures and, ultimately, protecting the public health.

Fauci’s agency (and the NIH) in turn had extensively researched which drugs to use for a SARS outbreak (remember that prior to COVID it was well known it was impossible to make an effective vaccine for SARS) and eventually, they concluded hydroxychloroquine was an ideal candidate to treat SARS.

Yet, once COVID started, Fauci did everything he could to conceal his agencies past research while simultaneously trying to cast doubt on each piece of data which emerged showing it treated COVID-19. Eventually, on March 19, 2020, Trump (whose administration was continually being pushed away from the drug by Fauci) decided to speak to the public about it, at which point the entire public health establishment begun a crusade to keep hydroxychloroquine [HCQ] from disrupting their grift (as were COVID to have become treatable, the trillions the billionaires received throughout the pandemic would never have been available to them).

One of the most remarkable ways this happened was by the WHO (and its related entities) conducting clinical trials which were designed to hurt (or kill) the subjects who volunteered for them. This was accomplished by:

•Only giving patients HCQ once they were severely ill (e.g., at the hospital). This was done because it was well known the primary benefit of HCQ occurred when it was given early in the illness, not late. So by “proving” it didn’t work late in the illness, that could be used to disingenuously argue it didn’t work at all, and hence was “unethical” to give early in the illness (which sadly worked).

•Give patients much higher HCQ doses (at levels were already known to be toxic), so patients receiving the drug not only didn’t benefit from it, but also did worse than the placebo group. This in turn was used to successful argue HCQ was extremely dangerous and hence not appropriate to give to patients (even though it was widely used for other conditions and long considered to be extremely safe).

Note: running deliberately botched clinical trials is a longstanding practice to discredit alternative therapies which threaten the more lucrative forms of treatment. Sadly, this was an issue long before COVID-19.

For example, Paul Marik was able to demonstrate giving IV vitamin C dramatically reduces the chance of dying from sepsis (which is one of the top causes of death globally). However, this only worked if it was done in the first 6-12 hours after arriving at the ER, so as you’d expect, whenever trials are performed, IV vitamin C was instead given long after that critical time point, which in turn was used to argue it did not work. Because of this, most hospitalists believe there is no evidence IV Vitamin C treats sepsis, and hence refuse to use it (even when specifically asked to by patients) so as a result, a lot of people have unnecessarily died from sepsis.

Similarly, in the 1970s, a promising alternative cancer therapy, laetrile attracted a great deal of controversy (to the point the FDA banned experiments from being performed with it). Eventually when enough public pressure forced studies to happen, Sloan-Kettering chose to use 1/50th of the dose that had been previously demonstrated to work, concealed the dose, and then relentlessly promoted that their laetrile trial had failed to demonstrate benefit (which was followed by using a variety of other tactics to conceal the positive results of laetrile once outside protest forced them to use the correct dose).

As we all know, the HCQ hit job was successful, and like many other therapies which proved themselves, patients (at least those who trusted the medical system) were never able to get them. One of the saddest illustrations of this came from lawyer Ralph Lorigo who filed 80 lawsuits on behalf of patients who were hospitalized and expected to die from the existing COVID treatment protocols so compel the hospitals to give them ivermectin. In 40 of the cases, he won, and 38 of those patients survived, whereas in the 40 cases he lost, 2 survived—which sadly demonstrated that suing a hospital was amongst the most successful medical innovations in human history.

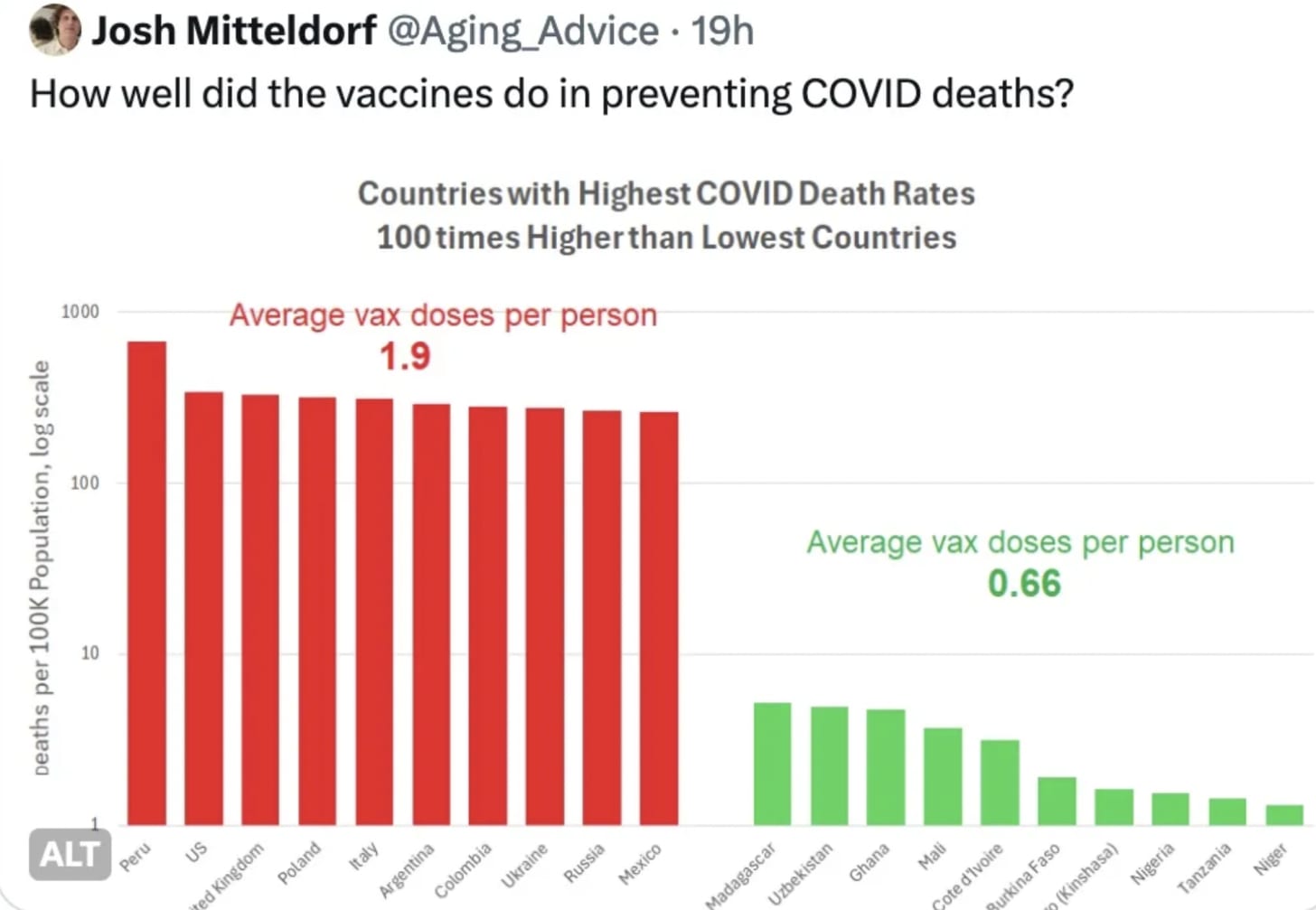

In turn, since (at least on paper) there was no effective treatment for COVID-19, this paved the way for the mRNA spike protein vaccines to enter the market, despite having innumerable safety and efficacy concerns which continued to grow the long they were on the market. This chart for example illustrates just how bad of an idea this was, especially when you consider that we spent almost 200 billion dollars getting them to everyone:

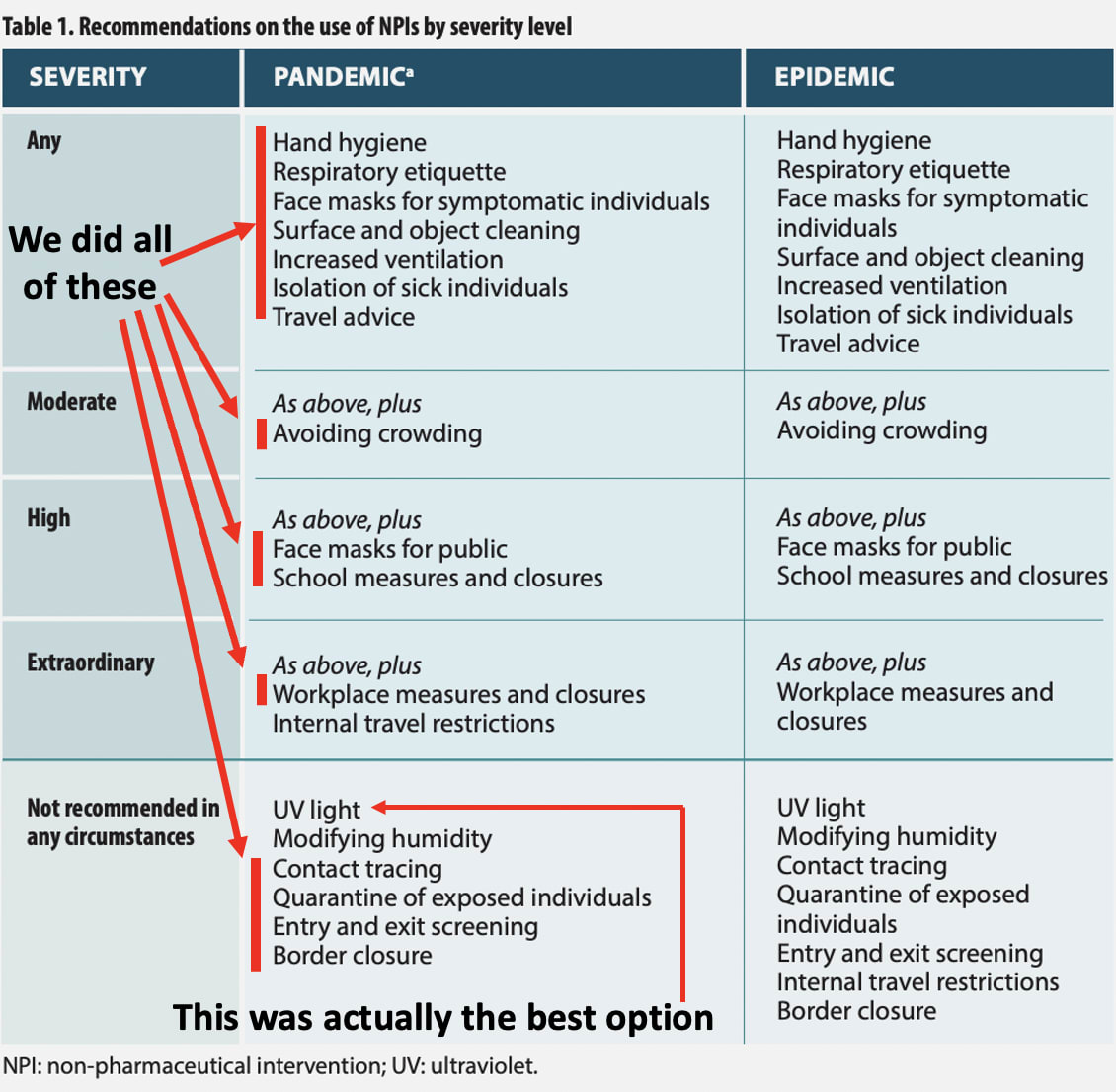

Additionally, in the same way the the longstanding practice of utilizing repurposed drugs was abandoned for COVID-19, many other guidelines the WHO had put into place were as well. For example, consider this guidance they had put together in 2019:

Note: a more detailed discussion on the value of using UV light to mitigate the spread of COVID-19 can be found here.

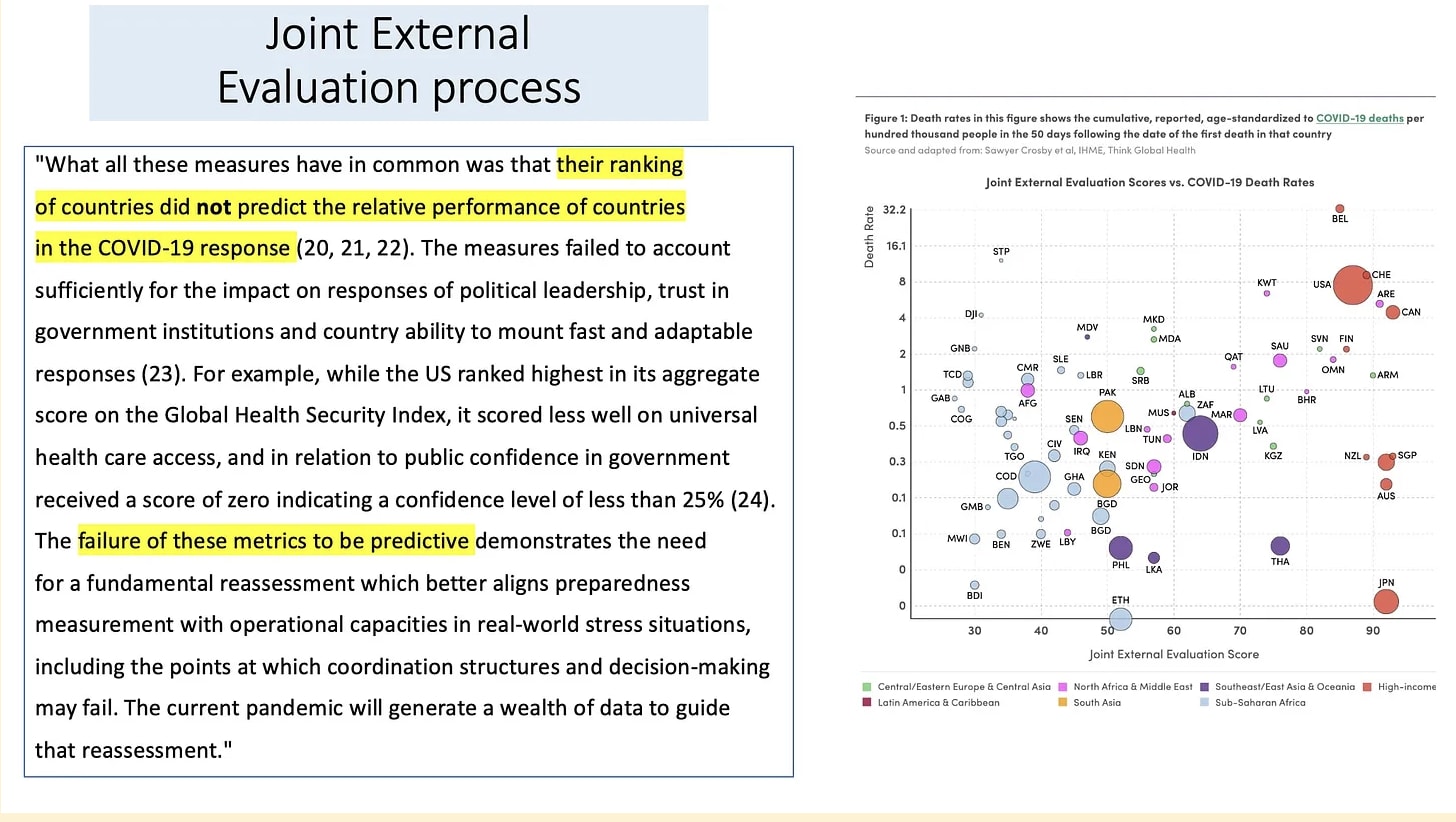

Eventually, the WHO was forced to evaluate how their policies had performed and made a rather “remarkable” discovery. The better a job a country did of following what the WHO told them to do (e.g., spend lots of money on their COVID-19 grift), the more people died.

These incriminating results prompted the WHO to investigate themselves, and as you might guess, they failed to hold themselves accountable for the greatest public health disaster in history.

Conclusion

Since the pandemic industry had remained mostly out of sight and out of mind, no one really paid attention to the fact they were taking the public’s money and failing to produce results. However, since COVID-19 affected everyone and the public was forced to listen to their lies over and over while simultaneously not being allowed to challenge them, this motivated many people to begin looking into what was really going on.

In turn, a vast network of independent journalists (funded by citizens who were understandably concerned about what was happening) gradually unearthed all the evidence which showed just how dangerous and unethical the pandemic grift was. The public (who were thirsting for the truth) listened, and gradually, the trust that industry had long depended upon was broken.

As a result, much of what had initially been project to occur (and a lot of money was spent to ensure) never came to pass. For example, the plan was to always have everyone take annual COVID boosters, yet three years out, only a small fraction of the population is continuing to boost.

This loss of trust is a huge problem for the industry as so many of their future plans are depended upon the public retaining their trust in them. In turn, I would argue that if the pandemic industry wants to regain the trust of the people it needs to demonstrate it will actually do its job and prevent future pandemics. This for example could be accomplished by:

•Banning GoF research.

•Committing to utilizing repurposed drugs to treat emerging pandemics and providing a way to protect the rights of doctors and patients to opt to use them.

Unfortunately, doing either of those will require the industry to give up its grift—so as you’d imagine, neither is being entertained. In the second half of this series, we will discuss what is instead being done and the heroic work individuals like Meryl Nass have been doing to stop it.